Neuroscience, Memory and Emotion: Enhancing Treatment of Anxiety, Depression and Traumaby Hannah Smith, MA, LMHC, CGP.

Course content © Copyright 2018 - 2024 by Hannah Smith, MA, LMHC, CGP. All rights reserved. |

PLEASE LOG IN TO VIEW OR TAKE THIS TEST

This test is only active if you are successfully logged in.

|

Course Outline

Learning Objectives Introduction Why Use Neuroscience with Emotionally Dysregulated Clients? Positives and Benefits Limitations Am I My Brain? What is Neuroplasticity? Pertinent Brain Structures, Processes, & Functions Brain structures & regions of interest Left-Right brain functions Sympathetic and parasympathetic systems Sensory processing Memory Learning Understanding Emotions States versus Traits Emotion Categorization Messages of Emotions Cognitive Meaning Physical Reactions Associated Action Urges The Process of Naming Emotions Functions of Emotions Regaining Control; Points of Intervention & Associated Techniques Conclusion References

INTRODUCTION AND COURSE OVERVIEW

One of the most common issues presented in therapy is emotion dysregulation. Virtually all mental health disorders present with emotional issues of some sort. Some clients present with “too much” emotion, reporting feelings of overwhelm and sharing stories of acting-out behaviors that are counterproductive to values and life goals. Others experience a dearth of emotion. These people talk of feeling numb, disconnected, and isolated. Suffice it to say, if you treat people with anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, personality disorders, trauma, you name it, you will encounter this issue. But, what are emotions and why do are they often so out-of-control or numb?

Great questions! I’m glad you asked! This module will attempt to explain that – and a lot more. First, you will explore the reason for studying neuroscience in relation to this subject. Then, a few important structures, functions, and systems of the brain will be discussed to lay a foundation for how emotions are generated and how they work overall. You will then learn how to identify and categorize emotions, what their functions are, and their specific messages. The overall process of naming emotions as they happen will be presented so that several points of intervention for positive change can be presented. Finally, from time-to-time throughout the article, Points to Ponder will provide thought-stimulating questions and/or ideas for practical applications related to the current section. Also, A Way to Think section will occasionally provide analogies or practical stories to help bring clarity or make the concepts easier to grasp.

The goal of this module is to help care providers understand some of the biological, experiential, and relational aspects of emotions and then to explain them to clients. Therefore, all throughout the module, there will be stories and anecdotes that help illustrate whatever has been discussed. Many ideas and techniques will be shared, but ultimately, you are the greatest technique available to those with whom you work. Once an understanding of emotions is ingrained, it is possible for you to bring your personality and experience in and create tools and approaches of your own. So, let’s go! Let’s dig in! [NOTE: Some sections in this article have been taken from another article by this author, entitled, “Neuroscience and Whole Person Care”. Although there are similarities that will work as a review, there will be differences as well. If some of it sounds familiar, though, this is why].

Why Use Neuroscience with Emotionally Dysregulated Clients

A client named Jeena comes in, flops down on the chair across from you, and, while sobbing, says, “I don’t know why I’m here. This is dumb. My boyfriend already told me that I was a lost cause – and then he broke up with me. I studied the wrong thing in college because I was trying to make my parents happy. That bombed because they are more disappointed in me now than ever. Either I cry, I yell, or I stare. I’m a mess. I don’t know what you think you can do!” --------Wow. What do you say to that?

If you’re anything like the clinician’s I’ve supervised, you’ve tried to explain that healing takes time…it is a journey upon which you are there to walk with them. Or, you’ve begun to take a lengthy history of everything that might have brought them to this point. You know the benefits of the process. You want to understand them, and you want them to engage. However, many people do not return to therapy after the initial few sessions because those who come in for care are scared, desperate, and in pain. They don’t want a process…they want a “quick fix”. This is not possible or even beneficial. Now, though, more than any time in history, we can use neuroscience-informed treatment to engage clients in a different, potentially more effective manner. Positives & Benefits

People experience emotional pain in a variety of ways. They may suffer from strong emotional experiences or the feeling of being numb. As previously stated, they want results – and they want them quick. Although we have come a long way toward overcoming the stigma of treatment, some people will still fear that “talk therapy” won’t be strong enough to help them. Understanding how the brain and body work can give clinicians an extra added measure of authority by which to help clients understand the benefits of therapy.

For some, it is more about reducing the intensity of the pain. One major reason people do not continue in therapy is that it “doesn’t work fast enough”. Neuroscience can help provide targeted approaches, thereby producing some relief relatively quickly. All therapists rightly understand that working through one’s life issues takes time – lots of time in some cases. However, this is a difficult pill for our clients to swallow. Techniques that soothe the brain and body can take the edge off enough to give people the strength they need to endure work.

Another tremendous benefit comes from the reduction in shame that comes from understanding how “the machine” (human brain and body) works. Shame acts as an “emotional infection” and distorts how people see themselves and others. It is pervasive and corrosive in nature. People with out-of-control emotions are pushed by compelling forces to do things that they would never do if they felt better. This produces shame that makes people not want to own their stories. Understanding how emotions and biology work can release people from this prison and make it safe to change the storyline without feeling so bad about what happened in their past. This is not an exhaustive list of benefits, but it is sufficient to lay the foundation for what follows. As you learn, you will undoubtedly discover other benefits. Limitations

As with anything, there are limitations as well. Most of us who will use this information are not neuroscientists. We won’t be able to answer everyone’s questions. This is hard for some, but it need not be. If you come across those who need more, you can refer them to books and articles for them to peruse (see Reference section for some ideas to start). It’s a learning process for both you and the client and you can be up front about that.

In addition to not being a neuroscientist, the field of science is constantly changing. What we know today may be obsolete or change to be near unrecognizable by tomorrow. There are also opposing views amongst scientists and practitioners. Some say that emotions emanate from the lower part of the brain while others say every part of the brain plays a role. You may be confronted by clients who bring in articles from online medical sites that spout a variety of points-of-view that may differ from your particular beliefs.

To combat all of this, it can be very helpful to speak in terms of concepts and ideas as opposed to facts and figures. This is how this module will work. “Ways to think about it” will be presented throughout. Whether emotions are created in the amygdala, the insulate, the cortex, or everywhere – the main concept is that emotions affect the body in common ways. You can say that and be right, no matter the particulars of a given school of thought or scientific study.

It behooves the reader to continue their study beyond this module. The information here is based on both current and traditional, fact-based (as best we know) understanding of the science along with over twenty years of experience as educator and practitioner. As such, this author has a particular experience and position and these will drive the method of presentation. Obtaining an understanding from a variety of sources is advisable. For now, you are invited on a journey of exploration as we investigate the incredible emotional being that we are. Am I My Brain?

Before we can talk about the brain, we must address a relatively odd question – are you your brain? ------- Huh? What do you mean? Remember Jeena? She had all kinds of negative thoughts about herself based on past experience. It seems she has taken those thoughts as truth. This is how many people see themselves. It is the, “If my brain says it, then it must be so”-syndrome. The truth is, you are more than your brain and emotions. You are a whole person. One way to think of this is to use two Greek words for “life”: Bios and Psuche.

Bios refers to the physical, biological life. The breathing, sleeping, eating, reproducing life. This is the realm of the brain, nervous system, and body as a whole. This is the physical, biological being.

Psuche is the life of the mind, referred to by some as the “psyche” or “soul”. In order to understand how to heal and rewire the brain, it is important to have the concept of the mind being something different from the brain and body. According to Psychiatrist, Dan Siegel, in his book, “Mindsight”, the definition of mind is, “An embodied and relational [entity] that regulates the flow of energy and information”. This energy and information can come from within the body (interoceptive) and outside (proprioceptive and relational).

For some, a third word, zoe, is also helpful. Zoe refers to the spiritual life. This takes into account the uniqueness and the social-relational aspects of the person.

A Way to Think. For our discussion, it may be beneficial to think of the brain and body as the car or the ship (where digestion is engine and brain is guidance system, for example), the mind is the driver/pilot/ captain, and the particular desired destination, preference for route (the thing that makes us unique) is the spirit. These metaphors help illustrate the difference between the various parts of ourselves. This is necessary in order to help one discern between biology and will. There are limitations with these images for sure, but it will serve nicely in this article.

Now that you know you are not your brain, we can begin the biological exploration. We will start with the overall goal – neuroplasticity – and work backward to understand all the various components. What Is Neuroplasticity?

Suppose you want a cup of coffee and you are in your car driving to work. After the (sometimes semi-) conscious awareness of wanting coffee occurs, it is unlikely that you would ever consciously think, “Pull car over. Put on brake. Stop car. Park. Left arm, open door. Left foot, step onto ground…” and so on. No. After the original decision to find coffee has been made, you somehow end up in the lounge in front of the automatic coffee machine. Ever wonder how that happens?

In short, from a purely brain-based, biological perspective, when you sought out and found coffee the first time, a set of neurons in your brain fired. The next time you want to find coffee from that same source (in that same place), the identical set of neurons will fire (provided it was an easy learn…it can take some time to create a fixed firing pattern). This is often referred to as, “the Hebbian Principle”, after Donald Hebb (1949). A famous saying coined in response to this is, “Neurons that fire together, wire together”.

All the various structures and regions of the brain talk to each other via what are known as “neural pathways”. These pathways are made up of millions of “neural connections”, the base element of which is a neuron. A neuron is a specialized cell that helps to conduct electrical impulses. Each neuron has dendrites – the “tendrils” that are attached to the central cell through which the electricity flows. Finally, electrical impulses jump between cells at a junction called a synapse. A single neuron can have thousands of dendrites and therefore make thousands of connections to other neurons. This happens as neurons “fire” in a patterned and connected way.

Imagine that a fly is coming at you. You will likely brush it away with a move of your arm without even being aware that you’re doing so. In such a case, a particular firing pattern is engaged as your arm “automatically” bats the fly away. As you can imagine, this “firing pattern” principle makes us rather efficient. In fact, if we do the same actions again and again, they become easier and eventually most will occur without conscious thought (generally through a process called “learning”).

Hmm…sounds like “neurorigidity” to me…Understandable. However, if you make the decision to grab your fly swatter, new or alternate pathways can be chosen as well. This is the work of the mind. In the brain, certain neuronal groups that frequently work together are referred to as “neural pathways” (or “circuits”) and may become hard-wired. Many people think of hard-wiring as innate, or “in us from birth”. This is not always the case. For our purposes, hard-wired means automatic, as many processes that come naturally to us were not present at birth. Several pathways that work together form a neural network. In action, this may look something like what is seen in the picture below.

Neural networks work together and form patterned responses in the brain. This is an amazing truth that is both wonderfully helpful but can be frighteningly problematic at the same time. Just as breathing carries on without conscious thought but can be controlled if one desires, so also with hard-wired neural circuits. When working on desired tasks, the efficiency of an automatic system is desirable. However, when responding in rote to that which would best be handled with flexibility, challenges arise. The brain, when left to its own devices, can land a person in trouble. Therefore, the flexibility of the mind is needed to make adjustments in brain circuitry (also known as learning). The ability to make these changes is neuroplasticity.

Pertinent Brain Structures, Processes, & Functions

The brain is immensely complex with manifold structures that interact in a myriad of ways. It is not necessary for the average care provider to know all the intricate details. What follows is a presentation of information pertinent to the treatment of mental health issues. A brief introduction to a few structures is included, but the focus will be on acquiring a working knowledge of certain systems, functions, and processes so the reader can understand how these affect our emotional experience. In addition, to help with understanding, each new concept discussed will likely include anecdotal stories to help illustrate the concepts and provide an idea of how to present the information to clients. Brain structures & regions of interest. The human brain is made up of the brain stem, Cerebellum, and four specialized regions called lobes. Each lobe has a right and left side separated by a membrane called the Corpus Callosum. Each lobe consists of many smaller regions that are responsible for a multitude of specific tasks. However, for this discussion, only the area of primary function for each major area is presented.

Starting from the back and base of the skull, there is the brain stem/spinal cord and Cerebellum.

The brain stem is responsible for basic life functions, such as breathing, heart rate, and swallowing (i.e. eating). Directly above the brain stem lies the Cerebellum, which facilitates communication between the brain and the rest of the body. This part of the brain regulates movement in the body and processes input from our senses. Even lizards and hedgehogs have a brain stem and Cerebellum. This is what is meant by “lizard” brain, though some people take it to mean “the brain we had when we were lizards”. This author does not ascribe to that meaning, but either interpretation is likely to work for our purposes. Above and behind the brain stem is the first major brain region, the Occipital lobe. This area specializes in processing visual information. As the brain is traced from lower back toward the front, the next set of lobes are the Temporal lobes, which are positioned in the skull near each ear. These lobes process auditory information, tags incoming information with certain memory and time-related tags, and process language. Moving upward in the brain will bring us to the Parietal lobes. The motor cortex and major sensory processors of the brain are housed here. Finally, the forward-most region is known as the Frontal lobe, which is the seat of awareness, executive functioning, judgment, and overall social behavior.

In order to better understand and explain the brain to clients, the brain can be thought of as divided into three main parts, also known as “the three brains” or “the triune brain”. Unlike the lobes, which consist of 4 sets of lobes and were described from base of the brain, upward and forward, the “three brains” can be thought of as lower, central, and outer structures.

The first, or lower, brain consists of the brain stem and Cerebellum. It is referred to in many ways, such as “the hind brain”, “the Reptilian brain”, and “the Lizard brain”. This area of the brain primarily focuses on survival and baser life functions. Moving directly upward into the brain is the “central brain” or “Mammalian brain”. This area is responsible for emotional and certain memory processing. “Fight or flight” originates in this part of the brain and it may also be called, “the emotional brain”. Finally, there is the “forebrain”, otherwise known as the “Cortex” or “Neocortex” and this includes the entire rest of the brain. This is where “thinking” occurs. Therefore, it is sometimes called, “the thinking brain”.

A Way to Think. To help clients understand, Dan Siegel created a “hand model” of the brain, which looks like:

Taking your lower palm and wrist to be the Cerebellum and Spinal Cord, the thumb is the Limbic region, the palm is the emotional center, and the folded over fingers are the cortex. When folded into a fist, the two central fingernails are the pre-frontal cortex.

To help clients form a picture, a simplification and analogy may be helpful:

Simply speaking, the lower part of the hand can be thought of as the “survival brain”, the cortex is “the thinking brain” and the central part of the hand is the “emotional brain”. Analogously, the cortex can be thought of as “a file cabinet”, the pre-frontal cortex is “the Secretary” or “Executive Assistant” (EA). “Couriers” or (for children) “Minions” run back and forth between the EA and the files. Some go on their own (like for heart rate), while others must be sent (as in when you attempt to recall a memory on purpose). Some can go on their own until compelled to do otherwise (the basis for neuroplasticity). We will refer to these analogies from time-to-time throughout the rest of the article.

Further Classification. Within the above-defined regions are further areas of specialization that are particularly important in understanding the role of neuroscience in mental health practice. These are listed in the chart below with their associated primary functions.

Working our way bottom-to-top, we begin with the Pons. This is a specialized, spider-looking structure that connects various regions of the brain together. Simply speaking, the Pons acts as the communication hub for the brain and also has some effect on sleep. This region is in the survival part of the brain.

Moving upward into the emotional part of the brain is the Hippocampus, which adds emotional tags to memories and holds those memories for later retrieval. Working together with the Pons, which aids in sleep, memory storage and consolidation are achieved (see Memory). Further up, but still in the emotional part of the brain, is the Thalamus. A major function of the Thalamus is sensory and motor relay – it is the part of the brain that makes us want to move when “fight or flight” is enacted. Interestingly, as it is in the emotional part of the brain. Therefore, thinking may not always be involved in the urges one feels.

The cortex is the rest of the brain that folds over the emotional and survival structures. The mechanisms and functions of cortex are vast and complex, but the primary focus is on information processing, especially in relation to interpersonal issues. It is useful to think of this part of the brain as geared toward “social survival” while the lower areas focus on “life survival”.

A crucial structure to point out here is an area of the emotional brain called the Amygdala. The Amygdala is often referred to as the “fear center” of the brain. This is an over-simplification for sure, but much in scientific literature and research shows the Amygdala to be an important structure related to the fear response. For our purposes, it will work to think of it in this manner.

A Way to Think. “Amygdala” is a tough word to say. It comes from the Greek for “almond” because of the shape of the structure. To better equip clients to gain distance from their biology and to continue to paint a picture of the “inner family” we all have, another useful analogy is “SAM”. SAM stands for “Search, Alert, and Mobilize” and is another innovative concept by Dr. Dan Siegel. Let’s give SAM a face:

SAM lives in the limbic and emotional areas of the brain and is responsible for the physical experience of anxiety (among other things). SAM’s job is to protect us, but he/she can be a bit over-zealous or misguided at times.

Points to Ponder. How would you explain brain structure at this point? Left-Right brain functions. The structure of the brain can also be described in terms of hemispheres, right and left. These hemispheres are connected via a group of fibers known as the Corpus Callosum, a thick bundle of nerve fibers that allow for communication between both sides.

Each hemisphere has very specific functions. The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controls the left. The left side of the brain is primarily focused on logical, linear, and linguistic activities. In other words, when you speak, do math, and think about the order of events, neuronal networks fire in the left side of the brain. An easy way to remember is: Left – Logic.

The right side of the brain is much more creative and flexible than the left. It is responsible for non-verbal and emotional processing, as well as random sequencing, and holistic perception. When you exercise, pay attention to your body, see images in your mind, or engage in expressive arts, the right side of the brain is engaged.

Traditionally, modern psychotherapy makes use of only a small part of the left side of the brain, as you can see by analyzing the figure above. Talking, therefore – especially abstractly – does not engage the whole brain. This needs to change if efficient and lasting progress is to be made.

Points to Ponder. What do you do that is not talk therapy? What is one creative activity that you can add to your practice? This may involve music, movement, or color. How will you explain it to your clients?

Sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. All of the human system functions best when it is in balance (otherwise referred to as “homeostasis”). In fact, it may be said that the overall goal of mental health treatment is balance within and for mind, body, and spirit.

Some structures in various areas of the brain and body work together for certain overall processes and functions that foster balance. These systems demonstrate how the brain and body rely on and inform each other. Examples of this process can be seen in the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. These systems (within the greater system of the person as a whole) work together to regulate physical states.

To work properly, these systems incorporate certain areas in the brain, some of the sensory system, and various organs and nerves along the spinal cord. The sympathetic system is responsible for the activation and acceleration of body systems and the parasympathetic system inhibits and slows down bodily functions. In short, the sympathetic system leans toward or engages in “fight or flight” and/or “up regulation” and the parasympathetic system results in “rest and digest” and/or “down regulation”. The following illustration points out what each system does with specific areas of the body.

You may be able to tell now, by just observing this chart, that over-active emotional states, such as anxiety and mania, are likely predominately “up regulated”, while depressed states are “down regulated” (depression, apathy). Think of all the presentations you’ve seen, namely pressured speech, shallow breathing, lethargy, and breath holding. Can you already begin to see ways you can make physical changes rather quickly? Let’s see it practically.

Right now, find your pulse. Take a few, quiet seconds to feel it. Do you notice anything? Now, take some deep breaths in and out. Do you notice it now? When you breathe in, your pulse quickens and when your breath out, it slows. Did you ever notice that before? You can see, then, how breathing can regulate the system.

A popular and specific form of deep breathing commonly taught by clinicians is known as, “diaphragmatic breathing”. Diaphragmatic breathing is a specialized way to breathe to calm and re-set the physical system. As some therapists are not fully aware of how this works, let’s look closer.

As demonstrated by our little activity above, when one inhales, the sympathetic system is activated (heart rate increases). Exhaling engages the parasympathetic system (heart rate decreases). Therefore, to do relaxation breathing correctly, one must breathe in (through the nose, to limit the stream) for a particular count (say 2 or 4), hold the breath (for, a count equal to the breath in count), breathe out through the mouth with some controlled force (as if blowing out a candle) – but always longer than when breathing in (say for a count double the breathe in count). Finally, hold breath again for a couple of beats. Repeat mindfully. Rapid breathing or simple “belly breathing” without the elements of control to activate the necessary system is not proper diaphragmatic breathing and may have limited results.

Note of Caution. For some people, especially those who hold their breath, diaphragmatic breathing could cause a sensation of lightheadedness or even claustrophobia. It is best to sit or lay down when first learning. Reassure the client they will be fine. Also, some clients experience what feels like claustrophobia or smothering when holding their breath. It is fine to limit the time of holding breath until the client becomes used to it and feels in more control.

Now, conversely, in depression, the system can be described as overly “down-regulated”. Here, a focus on engaging the sympathetic system via “behavioral activation” may be fruitful. Take clients for a walk, have them jump in place in the office, or have them make a list of physical activities they are willing to do (ones that get the blood pumping and the breathing a little quicker). Physical activity can return these systems to better balance.

Limitations. All techniques are limited by scope and particular area of practice. Be mindful of your and the client’s skill level before attempting a technique (do you fully understand, or can they see mania coming, and he like?). Make sure the client is cleared medically, if applicable. Sensory processing. As we move through the world, our brains take in stimulation from our surroundings and our own bodies and processes it into usable bits of information. Brain processing is not localized to only within our skull. It involves a stimulus, emotions, body responses, environmental cues, and cognition. As with the left and right hemispheres and the sympathetic/ parasympathetic systems, which perform related but different functions, likewise, there are two main systems involved in sensory processing. These are top-down processing and bottom-up processing.

Top-down Processing or front (Frontal lobe)-to-back (Occipital lobe) processing is known most commonly as top-down processing. With this type of processing, the stimulation in the environment passes first through the frontal lobe (where rules and previous learning are activated). The frontal lobe analyzes it and then stimulates emotion as a result and we respond. In other words, we apply thinking to what we perceive. By use of information and understanding we already have, we make and/or add meaning of what we see and experience. See the following example of top-down processing.

With something like this, you already know all the words, the syntax, and at least some of the context cues. Therefore, the perception of the words is made understandable by language rules you’ve already learned. As opposed to being able to understand:

Fgodaok, hgoy nem tduod ellvonasi ezt!

Looking at this, it may appear to be simply a bunch of letters grouped together. For native English speakers, that is exactly what it is. However, those born in Budapest, it may appear just fine, as the statement is Hungarian for “I bet you can’t read this one!” (Per Google Translate!) Unless you know Hungarian, your brain won’t make any sense of this. Therefore, the perception (words in front of me) is made understandable by cognition (rules for understanding words already in the brain).

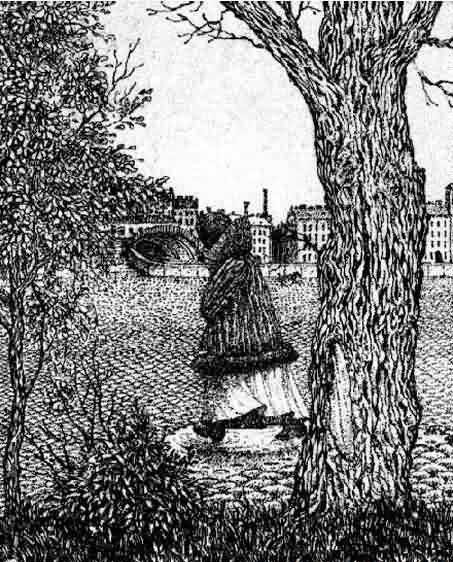

Back (Occipital lobe)-to-front (Frontal lobe) is more holistic and is known as bottom-up processing. This is a pure form of processing wherein the brain takes in stimulation from the environment first in the Occipital and Parietal lobes. Once analyzed, emotion is stimulated and then thinking may occur. This may be the type of processing most active in intuition and/or “gut feeling”. To demonstrate this, take a look at the following picture (you may need to blow it up some).

There are several pictures in one here. However, your brain first took in what you perceived as “the whole”. If you stopped there, you may label the picture as of “a man’s face”. However, as time went on, you added cognition and can began to see other things emerge, such as the lady in the coat and the canal tunnels. It is also possible, given your history and experience, that you either saw all the pictures instantly or that you saw the lady first and the man later. It depends on what your brain was able to interpret with “stimulus only”. Most likely, at some point, you would have seen only one aspect and the rest would have come as you pondered it. This is the same phenomenon that happens when a small child sees a horse but calls it a dog because it has four legs. This is “generalized” thinking and may be partly responsible for some anxiety reactions.

When not engaged, the amygdala does not trouble the body with the flood of neurotransmitters (such as adrenaline and cortisol) that are typically responsible for the subjective experience of anxiety (or jitters or nerves). Anxiety is evoked via the short path/bottom-up processing when the stimulation is perceived as a known threat. A soccer ball flying right at your face is a known threat and you will likely be out of its way before you are even fully aware it was coming at you. Clients who sit balled up and behind pillows in the chair across from you may perceive you as a known threat. Slow down. Take your time. They are unlikely to be aware of why (or even that they do) they feel that way.

The top-down, or long-path, is taken when thinking is necessary for analysis of the stimuli. For example, suppose you are walking down the street and you hear a fire truck. Initially, you might not feel nervous at all. However, once you have the thought, “Oh no! I wonder if it’s my house that is on fire!?” Then, instantly, panic shoots through your body. A clue that a client is experiencing this type of anxiety would be when they repeat themselves, ruminate, or express a great deal of worry. In such cases, a cognitive-behavioral approach may be a helpful.

There can be miscommunications within or misperceptions by the brain. The short path can be taken for benign stimuli and the long path can delay response when it is needed more quickly. In other words, we can jump out of the way of our own shadow and we can talk ourselves into holding still when our partner takes a swing at us. These misfires can result from internal or external issues and are often fodder for shame. A compassionate and “brain-based”/whole-person explanation may be very helpful.

A Way to Think. Imagine you go for a walk down the street. It’s a pretty day and you are admiring the foliage, when all of a sudden, you hear a siren blasting nearby. Internally, SAM is minding their own business, not bothered, but because it is a loud noise that indicates potential danger, the Thalamus Minion shoots a message to the EA. All was well until that happened, at which time the EA shouts, “Oh no! What if it’s my house on fire?!” At that point, SAM springs into action and the whole body feels like it’s on fire and has a massive urge to run. This is what happens in the top-down emotional experience of fear. Or, maybe when you were a small child, your bedroom was an odd color of purple/mauve with a patterned wall paper, like this:

Now, let’s say that every time you went into your room, your older brother socked you in the nose and took your toys. Not pleasant. Then, suppose you go to your first all-staff meeting at a new job and the room where they have the meeting has either this color or pattern on the walls. You walk in and instantly feel queasy and fearful. This is an example of when SAM decides for him/herself that a known threat is present. The EA may join in later and guess that the feeling has to do with fact that it is the first meeting. You find, then, that telling yourself, “I’ll be okay. I don’t have to talk this time” does not seem to work because it is not the current meeting is not SAM’s problem. You decide you’re going to fire your therapist.

That is, until your therapist tells you that you can’t really hear SAM, you can only feel him/her. Therefore, if you try a cognitive approach and it does not work and you know (or are fairly certain) there is no immediate danger, back it up with a relaxation activity and an overall “I am safe” approach to cover all the bases. Memory. Ah memory…the culprit in a great deal of mental health issues, as you may begin to see. The full treatment of memory is way beyond the scope of this lesson, but a few points will be explained to help lay the foundation for why emotions can be so troublesome.

Memory can be thought of as the encoding and storage of internal and external stimuli in such a way as to be retrieved at a later time. For fun, see if you can pass the following “memory quiz”:

As a way of exploring memory, let’s take these one at a time.

We are always conscious of our memories. False Memories are tagged and stored in many areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus, thalamus, parietal lobes, and frontal lobes. Much memory has to do with how we do things, such as walk or talk, or experiences we may not remember consciously. Therefore, we are not aware of all memory. Think, for example, of the time you asked your fidgety client what was upsetting them and they said they didn’t know. Their body does…

We accurately remember our experiences. False What did you do for your last birthday? What about Christmas? Think about it. What details come to mind? If your friend asks you, you may remember cake and presents. If your coworker asks, you may remember that you took the day off or had to work. Depending on the context in which something is recalled, the memory can change. In addition, our likes, dislikes, perceptions, and preferences can influence memory. If your favorite color is red, then you may remember a red boat on that fun trip you took last summer, only to be surprised to find a picture of a blue boat.

Memory is what we consciously recall about the past. False Like the example above, you may also have asked a client how their childhood was only to see them tense up. Yet, the client may say things were fine or that they don’t remember. This has to do with the kind of memory being accessed in the moment (see Implicit memory below for more).

The memory of past events can affect future function. True This is of huge importance. We tend to think of memory as something specifically about the past. This is true, it is about the past…but it is for the future. This means that memory is tagged and stored the way it is in order to make our ability to forecast and react appropriately in the future more and more possible. Think about it. Remember the coffee you go to get every day without thinking? If you didn’t have a memory of how you got there, what it was for, how much you liked it, and so on – then finding coffee every day would be a much more involved procedure.

Memories are like puzzles – they come in pieces. True Return again to the remembrance of your last birthday or Christmas. As you think about it, as you delve deeper into the memory, incorporating sensory information, you remember more and more. This is because memory is tagged and stored differently and in various parts of the brain. Some memories are tagged with language-based recall mechanisms and others are sensory or emotion-based. This is why a trauma survivor may remember the clock that was hanging on the wall but not the assailant’s face at first. Sensory-based, emotional memory may be stronger in some senses than word-based (see Explicit versus Implicit memory below for more).

Memories are primarily located in one area of the brain. False Memories can be stored and tagged in various areas of the brain. The location matters. Memories stored local to the parietal lobe may have time tags while those in the emotional enters may not. Can you imagine the implications of this?

Memories are only constructed by external factors. False Another important consideration – memory can be constructed by our internal states. This is why two people doing the same activity could remember it differently. If riding a roller coaster is thrilling to me but dreadful to you and we both do it, we’ll remember it differently, as well.

Memories can be changed and refiled. True This is good news (though it can be problematic, as well). Have you ever had a memory of something that was unpleasant, but then someone revealed something about it that you did not previously know or recall and then the experience of the memory changed? Yes – you can retrieve, modify, and refile memories. It isn’t an easy process, but it can be done. Think of the implication of this to relationship issues and trauma.

Many of the above references involved two important types of memory: Explicit memory and Implicit memory.

Explicit Memory, or declarative memory, is memory that is tagged and filed in the brain via language. It is “episodic”, meaning that it relies on contextual cues and experience. There is a sense of “time” inherent with it. Autobiographical memory is a type of explicit memory. It is clear both the right and left brain are involved with explicit memory as when asked about one’s last birthday, it is unlikely that mere lists of items and actions will be conveyed. Sensory setting will also be included. Remember, the left brain will provide the logical, linguistic-based information and the right brain will supply the sensations and images. Explicit memory is the type of memory most often accessed in talk-based therapy.

The other way of memory encoding is called Implicit Memory, otherwise known as procedural memory. This is primarily sensory-based, not time-tagged, and is the memory most used for “second-nature” actions. Try teaching a small child to tie their shoes or a teenager to drive a car and you will run into challenges of implicit memory. This may be the type of memory most troublesome in trauma as the retrieval of these types of memories can seem random and feel as if they are “happening in the now”. For all intents and purposes, then, flashbacks may be experienced by the body and brain as if they are actually happening again, resulting in a very real sense of being re-traumatized.

With respect to therapy, consolidation is an important memory-related concept. Consolidation occurs when memory is “properly filed” in the brain. In other words, it is what happens in the brain when neural pathways form a “trace” to a memory once it is “stabilized”. Memory consolidation is crucial for a sense of coherence and well-being. Consolidation may best occur when passing from short- to long-term memory (often via repetition or association) and/or during sleep. It is possible for the process to be interrupted and for files to be retrieved in some sort of error based on implicit, emotional tags. For example, if your birthday cake fell, you may remember “the whole birthday” as terrible or feel an actual knot in your stomach every time you hear the word “birthday cake”. When memory is misfiled (or, not filed at all but has a feeling of “floating around”), it can be reconsolidated. Reconsolidation is what happens when a memory is recalled and then re-stored.

Sit quietly (if you can) and close your eyes (after you read this next sentence). Try to remember your last birthday or Christmas (open your eyes when you have a visual image). Now, on a piece of paper, write down a few things you can remember from that occasion. Now…imagine your boss is asking you about the day. Write down more aspects of the day. Finally, imagine your grandma is asking. Write down a few more. Look at your list. Now, imagine your boss says, “Is that all you did?” and your grandma says, “That sounds lovely, Sweetheart!”.

Do you see any differences in the types of information you recall depending on who’s asking? Then, depending on how each person comments on it, you may “re-file” it with some color (or, lack thereof). It may be that the very act of conjuring up the memory changes it in some way, as does filing it after input. This makes reconsolidation an incredibly important therapeutic tool.

A Way to Think. A lot of examples preceded, but to further help clients understand, you can begin to talk more about the “file cabinet”. Thinking of the cortex (the entire top brain) as a file cabinet is a strikingly good analogy. All our perceptions, memories, and automated functions are in the file cabinet. The Minions (neural networks) are responsible for adding to and retrieving files. Sometimes, the Minions get lost. Sometimes, they retrieve things out-of-order. Sometimes, SAM is in charge of their dispersal and other times it is the EA. Ask your clients to ponder the implications and to start to try to guess how to improve the file system. Validate the fact that no one ever taught them this before, so they did the best they could. Even you, Therapist, could probably use a little tidying of the file system (as could this author!) from time-to-time. Learning. The final piece in the brain function that we will examine is learning, which is the foundation for all clinical treatment. Learning is a process by which experience and knowledge are acquired and integrated and it occurs with the help of all areas of the brain. In fact, it requires the entire body as well as the environment. Yes, the whole kit and kaboodle!

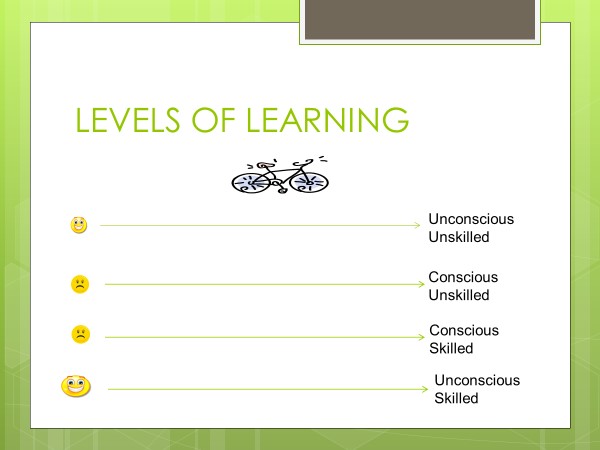

The process of learning begins at the point where we do not know what we do not know; before we know there is something to learn. This level of learning is called unconscious, unskilled. We are generally rather content at this place on the continuum. Here, for example, we would have no idea that bicycles exist and therefore do not care that we cannot ride one. Suppose, however, a time comes when we decide we want to learn to do ride a bicycle. That state-of-being is called conscious unskilled. As a rule, people are uncomfortable in this stage. We struggle with not knowing how to do something we want to do. This may be particularly difficult if we assume that simply knowing about something means we should know how to do it – a virtual mischief-maker in therapy.

Eventually, though, we jump on the bike and practice and learn to ride it. That is all well and good, but at that point, we use a great deal of conscious energy as we must think through every step over and over. This is where we hear complaints of, “It doesn’t feel natural”. We have many wipe-outs. This level of learning is called conscious, skilled. We really don’t tend to like this level of learning at all. Humans tend to want to appear as pros at everything at all times. Therefore, this is where most people would quit if not encouraged in some way.

With consistent practice (the length of which depends on many factors), we one day jump on the bike and off we go – no highly conscious thought involved any longer. This final stage is called unconscious, skilled. Here is an illustration:

This last stage is where we spend most of our life (also known as “automatic”) and it is the place where we are happiest. Well, until we’re not. Sometimes, we learn something that is not really all that effective for us. For example, if a parent was covert in how they spoke with us and questions were disguises for digs and insults (such as, “Don’t you want the light on, Sweetie” as code for “What are you, lazy? Can’t you turn the light on by yourself?”). If this is our experience, we could hear all questions as accusations and may snap at anyone who asks something. If this type of learning occurs, would we have to start all over? No, we couldn’t go all the way back to unconscious, unskilled because we already have awareness. We may spend some time on the second level, learning skills to which we were not previously exposed – but mostly, we will have to use what we have learned in a very conscious, careful manner in order to become more proficient at skilled use. It is important to note that this process requires repetition and/or association in order to work well. There must already be something in the file to attach to, so to speak, or one must try to add new information repeatedly. This is why a person may find themselves acting as if they believe something they actually do not – simply because they’ve been exposed to it so many times or it “sounds” or “feels” right because of association.

Finally, the entire process can be thought of as being bypassed when trauma occurs. During a trauma, all the fine details are not learned in the typical way and therefore we have more of an “imprint” of learning as information is stored more in implicit, sensory-based emotion than explicit, language-based memory. Even emotional experiences themselves (overwhelming guilt, shame, or fear, for example) can cause us to “learn” something.

Whatever the process or method of learning, those of us who provide care to people with mental illness often have to take people back to level two or three – very uncomfortable places – in order to help them acquire more effective skills. Knowing this, we can communicate early on that therapy is a learning process and the goal is eventually to reach unconscious, skilled; automatic; easier. This can relieve some distress along the way. Understanding Emotions

This author works at a partial-hospital, mental health rehabilitation program called, The Center; A Place of Hope, in Washington state. Many people who come here for treatment make the following statements:

Emotions are weakness Emotions are random Emotions are overwhelming I cannot feel any emotions Emotions are useless/stupid

You’ve probably heard similar statements. How do you respond? How do you explain emotions to clients? To listen to what most people say and to watch their behavior indicates a general misunderstanding of what emotions are. Technically, as you learned above, emotions are chemical/electrical-based responses to internal and external stimuli. Another, more client-friendly way to say that is emotions are “a biological signal system” – short and sweet. Therefore, emotions are no more a weakness than a traffic light is. The feeling of emotions being “random” may come from not understanding them as transient. To understand this, let us discuss emotions as “states versus traits”. State versus Trait

As emotions are a response to stimulation, both internal and external, they vary and are best thought of as a state or states-of-being. To illustrate this, let us assume it is our friend, Treya’s, birthday. Secretly, she is expecting a surprise party. As she arrives home and reaches to open the door of her house, she brims with excitement. However, as she enters her darkened house, she finds no one is there to yell, “Surprise!”. She will fall quickly into disappointment and melancholy. However, if she has some crafty friends who enjoy making her suffer and don’t jump out at her until she’s been in the house for some time, she will rapidly rise to joy the instant they pop out at her. All of this variation in emotional experience occurs in the space of a very few seconds or moments.

In our society, we are encouraged to “pursue happiness”. All the commercials and advertisements we see tell us we should feel happy or excited at nearly all times. As described above, learning can happen by repeated exposure to a stimulus. Therefore, a great deal of dissatisfaction and emotional distress in life can come from the belief that we are meant to feel a certain way all the time. This is highly unlikely in even the best of circumstances.

There are occasions when a person is labeled with an emotion word. For example, one might say, “She is such a happy person” or “He is a rather grumpy old man”. These terms are used as traits. Traits, in this case, are apparently enduring presentations of an emotion. However, the “happy person” can feel sad and the “grumpy person” can feel happy or playful. What is demonstrated here are a set of choices, beliefs, or actions that present an overall picture. As we discuss emotions in this training, we refer to the biochemical, transient experience in the body and not to a labeling of behavior or temperament. It is easy, however, to see how people can have the feeling that emotions are random. The fleeting nature can make it difficult to ascertain their cause at times. There is, however, a cause, and it is not random – it is non-conscious. A discussion of emotional categorization may help with this. Emotional categorization

One may think it necessary to learn first about emotional identification rather than how to categorize them. Actually, though, the naming of an emotion is much more complex than one might initially assume. Therefore, it is important to start from the big picture and work our way down to smaller details. Emotions, for this discussion, can be categorized as primary and secondary. Tertiary emotions also exist but will not be covered here.

Primary emotions. These are the emotions we feel first in response to a situation. If you look up “emotion wheel” (see Fig. 14 below), you’ll see many different versions and several primary emotions are listed. However, common to all (usually) are anger, fear, sadness, and happiness. These are generally the most basic, most transient, and strongest emotions felt by the body, and therefore the easiest to identify when we have time to notice them. Primary emotions occur before secondary emotions.

Secondary emotions. These are the emotions we feel in response to a primary emotion. Take the example of when my stepson startled me one evening. As I walked into his bedroom to get something, he was hiding under some blankets on the floor and he reached out from under them and grabbed my leg. As he did that, I screamed and jumped. That initial emotion was fear. However, by the time I hit the ground, I would have said I was angry. The anger was not due to my stepson. The anger was due to feeling fear, which I do not like or did not expect or need to feel. The reason it may look like it was my stepson is because the secondary emotion tends to stay around long enough to give my cortex time to find a source to blame.

Aren’t we something? We are so hard on ourselves and others when we or they play the blame game. It is not effective, for sure. However, blame is a biological function in some ways. It keeps us alert to danger. However, as we will know well by the end, the cortex does not always get it right. Now, study the emotion wheel below.

Suppose your primary emotion when given a promotion at work is surprise. Really imagine it. You sit in the chair and hear the words, “You are now the new…” How do you think your body would feel? How long would it last? Now, after the initial surprise wears off, your brain says, “Was that good or was that bad?” As a promotion is generally thought of as a good thing, we’ll say “good”. The options for secondary emotions to surprise range from startled and confused to amazed and excited. It is possible to pass through both of those, feeling both excited and amazed. On your drive home, if you check in with yourself and see how you feel related to the promotion, though, by then you might say “eager”, if you accepted what happened and want to get on with the work. Or, you might say, “astonished” if you still have a hard time believing you got the promotion.

See how that works? Look back at the “surprise-not surprise-surprise” party above. Using this particular wheel let us slow it down to microseconds and examine a likely scenario. At some point in time, Treya most likely had a thought something like, “Today is my 30th birthday. My friends like me. They will surely give me a surprise party!” The stimulus in this case was this line of thinking and the resulting emotion was surprise (a brief “ah ha” at the whole idea of the party), which resulted in a secondary and more enduring feeling of excitement. When the door was opened to the dark and quiet, there was an initial feeling of disgust at the fact that her loving friends actually abandoned her. This resulted in the feeling of disappointment. Once they finally jumped out at her, surprise and a feeling of excitement returned. Later, if asked to recall her emotions, she would likely say, “I was excited when I opened the door, then disappointed, then surprised.”

Two secondary and only one primary emotion are recalled. What happened? The stronger (surprise) and/or more enduring emotions (excitement and disappointment) are easier to recall. Also, the reaction of surprise at her own thought was less in comparison to the surprise when the party actually commenced. Finally, no one likes to admit the feeling of disgust at their friends, so the brain learns to ignore it. As you read through all of this, were you able to have a sense of each emotion along the way as it was named? Pretty amazing, isn’t it?

Points to Ponder. Think of one of your own emotional experiences. Can you figure out your primary and secondary? How would you explain this and what would you do to lead someone to find theirs? There is one more categorization of emotions that can be helpful to know but does not appear on the wheel. It is instrumental emotions. These are the “amplification”, as it were, of the primary emotions. For example, being angry that you are angry, or afraid because you feel fear. These can be conscious or non-conscious. Instrumental emotion is a concept used in Emotion-focused Therapy (EFT).

Put all of this together and, again, if one does not know what is happening, it is easy to understand why emotions feel random. In the example above, it may have initially seemed as if the excitement morphed into disappointment as most people would not have been able to identify the disgust. Who has time these days, or even the emotional vocabulary, to name the specific emotional state one is in at any given moment? To do this takes something called, emotional granularity – or, the ability to differentiate between various emotional states. As you can see, learning to work to improve this is important. Messages of Emotions – Mind-body Connection (Feeling, Meaning & Actions)

I hope you are starting to feel you are growing in understanding of these elusive things we call “emotions”. We now understand that we experience layers of reactions to what happens in and around us. The sifting is the stuff of therapy as it is not always an easy process: the passage of time, likes and dislikes, and many other elements contribute to our current interpretations of our emotions. Let us work more on the idea of emotional granularity by learning more about emotions, which can help us more easily identify them.

Sticking with the four primary emotions that are most common to all emotion wheels, you may be happy to learn that there are body sensations, need/want-based, and resultant action urges associated with each! There is some debate on this, but for all practical purposes, most research and conventional wisdom show us these seem to be experienced by most people in some related form. Go ahead and be skeptical. Think it through. See what you come up with.

Body responses or “sensations”. When emotions are felt in the body, neurotransmitters and hormones release to cause particular sensations. There are a variety of these, but most people would admit a trend. Let us look at the four primary emotions we mentioned before.

Anger. Think about the last time you were angry. What happened in your body? Most people report feelings of muscle tension, jaw clenching, making fist, maybe even dry mouth or excessive sweating. However, one common feature is heat. Anger comes with physical energy.

Fear. What about fear? How do you tend to feel when afraid? Again, there are a plethora of responses, but most people report sensations such as feeling cold and/or jittery.

Sadness. Frequent somatic complaints with relation to sadness are feelings of heaviness or emptiness.

Happiness. Not surprising, lightness and fullness or satisfaction are the physical responses to happiness (often thought of as the opposite of sadness – interestingly, that seems to be the case on all levels).

These are certainly simplifications, but as mentioned, we simply need a way to think about all of this that is helpful and useful for clients. physical reactions listed above make sense once we also learn the typical messages brought by each feeling.

The Messages of Emotions. It is not always possible to figure out the antecedent events that cause primary emotions that lead to the secondary and tertiary ones we bring to therapy. However, there are some guideposts that can help us at least have a place to start to figure it out. Again, there will be some variation, but as feelings go, most emotions have two or three particular messages that produce them. This one fact, beyond all others I have ever taught at The Center, brings clarity and catharsis as well as further credence that emotions are not stupid or weakness. They are, in fact, an elegant alert system. The most important thing to know up front is that they are not always accurate – but more on that later. For now, let us marvel at the wonder our emotions are.

Anger. When was the last time you were angry? Have you ever been told you’re “not supposed to be angry”? You may definitely change your mind on that now. Anger tells us something. It’s not just selfish reactions to not getting what we want – at least not in its most base form. Anger tells us that something unjust has happened or that a boundary has been crossed. You can see this in the secondary emotions on the wheel: aggressive, frustrated, distant, critical can all be associated easily with injustice. Hurt, threatened, hateful, and mad correlate well with boundary crossing.

Fear. The messages of fear are danger (not a big surprise, I’m sure) and the unknown. Take a look at the wheel. Do you see it?

Sad. Sadness tells us there has been a loss to grieve or mourn. It also points to unfulfillment, which may be a surprise to some. Don’t underestimate the importance of chronic boredom. It may be trying to tell you something. We all need to have a sense of purpose.

Happy. Well, if sadness is loss, then happiness is gain! However, there is a caveat. Gain is not the acquisition of more and more and more without limit. Attainment of “stuff” can often act counter to our sense of fulfilment, another earmark of happiness. Think about what that means in our society, where we are frequently told that the pursuit of things will make us happy. Will it really? Can it?

Look again at these messages above. These categories may provide a direction when unsure of what emotion one is experiencing. For those who subscribe to the “emotions are weakness” thought - think about your best friend. Would you want them to know when a boundary is being crossed? Do you want them to feel safe, and to know when a loss has occurred? Think about people you know who act as if they never experience a loss or an injustice. How do they move through life? Emotions are crucial and helpful. I second Marsha Linehan’s encouragement for us to “love our emotions” (see her DBT Training Manual). Without an understanding of all this, though, our clients might laugh in derision at that statement. A last aspect of emotions we will look at in our attempt to identify them are the action urges associated with them.

Action urges. Understanding that our biology is wired to react quickly (remember, SAM is much faster than the EA) is a key in reducing feelings of shame when we analyze our reactions. If we could have seen our party-goer above when her friends didn’t surprise her at first, we may have noticed a facial grimace, some negative self-talk, or even an urge to flee the situation in repulsion. Once the party actually happened, though, she would most likely deny (on some level) ever having an urge to do those things. However, if caught on camera, she may have felt embarrassed. The truth is, the body does what the body does, and we just need to understand that it is trying to communicate with us. Here’s a “dictionary” of emotion-based physical reactions.

Anger. I probably don’t even have to ask this – but what do you typically want to do when you are angry? Yup! You got it! Yelling, hitting, stomping, actions that indicate fight!

Fear. You may guess this one quickly, too – when in fear, we want to get away, or flight (flee). Think about it. If there is danger, it’s best to be somewhere else. What about if you feel rejected or “less than”? Isolation is a normal response as pressuring others to accept your presence rather than wanting it of their own volition is coercion – and a healthy relationship cannot be coerced. Our bodies are pretty smart, aren’t they?

Sad. What about sad? Here, it gets a bit interesting. Many people report a drastic reduction in motivation, which I have called, stop. Very sad people do not tend to want to move or connect with others.

Happy. You guessed it. Happy is go.

Pretty interesting isn’t it? What about that fight and flight? What about that stop and go? Lots of patterns (and no, “sad” is not “freeze” – that is something else entirely out of the scope of this article). Once you know what you are looking at and for, it can become so much easier to unravel the mystery of naming our emotions. Still, for some people, their emotions are so big or so absent that to even start with these classifications could be too much.

Pleasant/Unpleasant. When clients report having too many, too strong, or absent emotions, start first with the idea of “pleasant” or “unpleasant”. There are two main reasons for this. First, simple binary categories are always easier to identify as compared to more detailed emotions. “I feel good/not good” is much easier to ascertain than attempting to identify something more refined, such as, “I feel repugnant/loathing” (or whatever). From this place, it’s easier to narrow things down. Also, simply labeling an emotion as pleasant or unpleasant reduces judgments, which in and of themselves are emotionally inciteful. We want to do anything we can to simplify emotional identification.

The above discussion is summed up in the chart below.

The Process of Naming Emotions

As if it isn’t enough that emotions can be identified by their associated body sensations, messages, and action urges, there is also a specific process that occurs to name our emotions. Learning this process will provide a deeper understanding of how emotions in the human body are formed and demonstrated and, later, will yield several points of clear intervention for positive change. What follows are various pieces of the emotion puzzle. Hang on, it’s going to get really good now!

Where it all begins. The naming of emotion does not start with the emotion itself, though that often is how it seems. We do not feel sad, happy, angry, or other emotions without a catalyst, and internal and external reactions of some type. Commonly referred to as the activating or prompting event, it is an internal or external event or stimulus that triggers emotional response. We may or may not be aware of these events, which is often why people have the feeling emotions are random or “dumb”. Carrying on with our earlier example of Treya and her surprise party, there were essentially three prompting events, starting with the internal thought, “Today is my birthday!”. The second was when she actually opened the door, and the final one was when everyone jumped out. For our discussion, let’s use the “when she opened the door and no one was there” event.

Interpretation. All events that affect us have to be given some sort of meaning. For example, Treya might have thought, “I have terrible friends”, which would lead to the feeling of disgust and then disappointment. However, for the same event, Treya could have thought, “I bet my friends are waiting until another day to really surprise me,” or, “I bet they don’t know it’s today,” both of which would lead to more pleasant reactions. The interpretations are the meaning we ascribe to a given event, whether we know it or not.

A Way to Think - Valid versus Accurate. Interpretations (and their resulting emotional states) are always valid, however, they are not always accurate. Consider a classroom full of six-year-olds who have been instructed to spend the last ten minutes of class coloring. At the end, little Suzy goes to her teacher with delight on her face, showing off her drawing. Should the teacher respond by saying, “Oh my! What a lovely drawing! Good job!” Suzy’s experience of appropriate pride will be reinforced. If you give her crayons again, she will color without reservation.

However, should the same situation occur and the teacher respond with a reprimand, such as, “What’s wrong with you? You know that frogs are green! What’s the point of a purple frog? How silly. Go try again!” Deflated, this little one may not entertain coloring again.

What did Suzy learn in the latter case? Did Suzy actually do anything wrong? Where was the “wrong” in this scenario? You likely rightly said with the teacher – however, it is Suzy who learns, “I am a bad artist” as her interpretation of herself.

Therefore, due to poor responses from our inner world (such as self-defeating thinking) and our environment, we can learn something that is not actually true. It behooves us, then, to pay particular attention to our ineffective interpretations and to question their origin. More on this later when we discuss ways to address emotional issues.

Pre-existing vulnerability factors. Although the cycle of naming emotions actually begins with the prompting event, pre-existing vulnerability factors, as implied by the name, are the beliefs, situations, experiences, bodily states, or other factors already present at the time of the prompting event. For example, suppose Treya’s skipped breakfast and did not sleep well last night, or her best friend has been upset with her for a few days. When we are tired, hungry, emotional, or have similar unpleasant experiences in the past, we will draw from these to formulate our interpretation. From above, if she thinks, “I have terrible friends”, it could really be that she has terrible feelings in her body, so that colors everything. Or, perhaps a memory stream from childhood is triggered that make her remember a time when she was bullied and no one came to her birthday party. However, if she is secure and has many happy experiences, she will likely choose something in favor of her friends. All of this can happen rapidly and without much (if any) conscious input.

Internal changes. Once the prompting event occurs and the pre-existing vulnerability factors color the interpretations, a cascade of internal experiences occur.

Brain changes. Once an event is given meaning that indicates a need for reaction, certain changes occur in the brain. These may include the release of particular neurotransmitters and/or the strengthening or weakening of a given neural firing pattern (or pathway). For Treya, her initial brain changes may have included adrenaline and serotonin (neurotransmitters), and if she has not had good experiences with friends or birthday, then the pathway that says “friends not good” would be strengthened.

Somatic changes. Adrenaline and serotonin can result in a myriad of experiences, such as a raise in blood pressure and heart rate, or a change of blood flow to muscles, and an overall feeling of relaxation.

Sensations. The above experiences result in particular sensations in the body. For some, the somatic experience of jitters and racing thoughts signifies excited anticipation. For others, the same physical feelings result in dread or fear. It all depends on the severity, the pre-existing vulnerability factors and interpretations.

Urge to act. As discussed above, emotions tend to be connected to particular action urges, such as flight, fight, stop, and/or go. Different people may have different levels and intensities and some emotional experiences tend toward inaction. However, we are biologically prone to act in our own benefit in such a way to either protect ourselves and/or to cause the most effective and beneficial background.

External changes. Not only do we experience somatic and internal changes, we demonstrate these changes outwardly.

Body Language. Most likely, Treya rolled her eyes, sighed, moved with crisper, more deliberate and strong movements or some other type of body language. When the interpretation sets the internal world on a trajectory, it is difficult not to show it on the outside. Tone, posture, and gestures are all often contingent on the inner experience.

Word choice. In addition to our way of communicating, we may also choose words to describe how we feel. “Terrible friends” versus “forgetful friends”, for example. You guessed it, also as a result of our interpretations.

Actions taken. Slamming doors, stomping, yelling, bolting, pouting, hugging, shutting down, and many more, are all actions we take in response to our current emotional state. As you will see, they communicate our emotional state to ourselves and other.

Actual naming of emotions. All of the above works together to produce our emotional experience. If we pay attention quick enough, we can name our primary emotion. However, it can be several cycles in before we actually know how we feel. The process of naming emotions can be seen in this chart.

After effect. As you can see from the chart, once we name our emotion, we have an after effect. It is this after effect, which leads to another prompting or activating event, that we react to with secondary emotions. Treya thought her friends were terrible initially. Had they not been there, the after effect may have been the thought, “No one cares about me”. Can you guess what the rest of the cycle would look like then? Or, “I better give them a call”. What would the process look like then?

Functions of Emotions

Now that you understand about messages, sensations, urges, and the process of naming emotions, it is important to discuss the reason we have emotions in the first place. Identifying both emotion and purpose can help with choosing an intervention. First, consider separating emotions into two groupings: hard-wired and situational. For this discussion, hard-wired (or, automatic) emotions are those that are important to feel in the given situation. Should a hundred people be in the situation, they would likely all react in a similar manner. When a cougar chases you, run. This is a hard-wired, emotional response. Situational responses are those that may change due to a person’s particular process. Roller coasters excite some people and scare the tar out of others. Keep these in mind as you read.

Communicate. Emotions help us to communicate with others. As we interpret our inner and outer worlds, emotions show up on our face and in our actions. When it is important (hard-wired) to send a particular message, such as in expressing alarm or joy, we will often do so without awareness. Can you think of a time when you conveyed a message on your face or with your actions that you did not want or mean to convey? What was the circumstance? How did you respond?

Treya’s initial response was meant to convey excitement and happiness. This message, when seen by others, is reinforcing and they may be more likely to bring her surprise gifts in the future.

Points to Ponder. Give it a try. Over the next few days, find times each day to pay attention to your behaviors, word choices, and thoughts. As you feel comfortable, ask for feedback. Do you notice what you are attempting to convey?

Motivate. “Watch out!”

Ever heard that? When you did, do you remember stopping to consult your cortex as to why you needed to watch out? For what? Something falling? Or, maybe jumping? Something big or small? A person or a bug? What? Likely, you didn’t think of any of that. Rather, you simply jumped out of the way. “Move now, ask questions later”. This is also a function of your emotions. To get you out of the way, or to prepare you to fight, flee, or freeze.

Validate. This is a complicated one and what is most affected in situations such as anxiety, depression, and trauma. Whenever we do something, such as conceive an idea or accomplish a task, dopamine and other neurotransmitters and hormones are released that “reward” us with pleasant feelings. However, some of the steps between “idea” and “accomplishment” are not so rewarded. Also, certain mental illnesses come from an imbalance of the chemical system in the brain. Therefore, one may not receive the typical body signals and misinterpret. Let us look at an example.

Rian is depressed. You ask Rian if he wants to go to the movies and he moans and complains and says no. You push him, and he eventually relents and accompanies you. While at the movie, Rian is able to laugh and appears to enjoy himself. However, when you see Rian tomorrow and check in with him on how he enjoyed the movie, he will again mope and indicate it wasn’t all that fun.

What? You saw the smiles and heard the laughter with your own ears.

This is what happens when we struggle with lack of motivation in depression. Our “recall” and “forecasting” systems are colored or depressed as well.

Typically, when you do something, such as eat a new flavor of ice cream, your body records information and your “reward” system lets you know if it’s pleasant or not. You record that information often as a “like or dislike” or a “want or don’t want”. As this system is impaired in mental illness, you may think you don’t like or want anything. The truth is – remember – you are more than your brain. Your engine doesn’t have to feel like working to work. You don’t have to want to do something to do it. That is the magic and mystery of being mind and spirit as well as body and brain.

If you are a person who feels they do not know themselves, then paying extra attention to this system (when it is working well) will alert you. The language of emotional validation is fairly binary: Like/don’t like, want/don’t want, approve/don’t approve, and the like. When something goes awry, the common result is resentment and repulsion. Clients often feel angry at themselves for feeling these, but they are important messages. There. Now you have it! Now you understand emotions, their messages, functions, and the process of naming them. There’s a lot to it, but once understood, it gives credence and clarity to so many aspects of life.

Now, let’s take a look at naming emotions again and use this as our guide in providing relief and treatment of inflamed and infected emotions. Regaining Control - Points of Intervention & Associated Techniques

Take another look at the process chart from above:

Take a good, long look from left-to-right. Can you see ways you can intervene for positive change? What follows are various techniques and ideas you can use along the way to intervene. However, as mentioned before, you are the greatest strategy there is. Apply your uniqueness to this. Stop reading now and write down some ideas of your own, then return and read through the information and suggestions below.

Awareness and accommodation. Let’s start right at the top, with pre-existing vulnerability factors (PVF). Remember, these are those events, memories, perceptions, and thoughts that come from your experiences. Some of what we do in therapy is to take a look at family and experiential history to figure out what some of these PVFs are. Interviews, assessments, histories, and mannerisms can create windows into this. However, as most people who seek help do not really understand what is happening within themselves and are not aware of what they do each day, they may not be able to clearly or directly state what experiences are bothersome. Therefore, another strong first step (and way to achieve mindful living) can be to raise their awareness of what is occurring in their bodies, minds, and lives throughout each day. Many clinicians try to encourage this by asking clients to “check in” with themselves. However, this may be too vague. Once they check in, they may struggle with knowing what to do with what they find.